The Academy Awards are a celebration of incredible talent in film, but the most memorable cinematic performances often owe as much to visual storytelling as great direction or scriptwriting. Wardrobe choices can shape a character’s identity and leave a lasting impression on audiences. This year’s Oscar nominees made a distinct impact not only through their acting but through the defining costumes their characters wore on-screen. Let’s take a closer look at four of the nominated actors—Robert Downey Jr., Ryan Gosling, Mark Ruffalo, and Bradley Cooper—and how their film looks helped elevate their performances.

Robert Downey Jr. in Oppenheimer

Robert Downey Jr.'s turn as Lewis Strauss in Oppenheimer is one of disciplined subtlety and layered ambiguity. The costuming for Strauss was integral to establishing his complex personality. Throughout the film, Strauss is commonly seen in conservative, era-appropriate suits—gray or navy, always immaculately tailored, paired with crisp white shirts and restrained ties. The sharp lines and formal silhouettes not only placed the character in the anxious, high-stakes milieu of postwar Washington, but visually communicated Strauss's meticulousness and need for control.

As Strauss becomes more adversarial and scheming, his outfits grow even more buttoned-up, reflecting internal tension and rigidity. Downey Jr. uses these tight, formal clothes to reinforce the character’s emotional confinement. Even the color palette—never flashy, always muted—mirrors Strauss's understated but forceful presence. The costume’s formal austerity made Downey Jr.'s restrained physical performance even more compelling, letting slight shifts in gesture or posture feel deeply revealing within the boundaries of immaculate tailoring.

Ryan Gosling in Barbie

Ryan Gosling’s Ken is one for the ages—and not just because of his scene-stealing musical numbers. The film’s wardrobe department went all-out in constructing a fantastical, hyper-stylized vision of male Barbie fashion. Gosling is introduced in pastel jackets, sport shorts, neon rollerblading outfits, and denim-on-denim looks that are both exaggerated and instantly iconic.

These bold costume choices are central to the character’s comedic journey. Ken’s quest for identity and relevance is rendered in every outfit, from the beachy pink windbreakers to the outrageous white fur coat for his “Mojo Dojo Casa House” phase. Each look amplifies Gosling’s comedic timing; his self-serious delivery, when paired with candy-colored or absurdly macho ensembles, becomes both hilarious and endearing. The costumes helped Gosling fully inhabit Ken’s oscillation between earnestness and absurdity, making the character’s emotional arc both visible and unforgettable. Not only did the costumes support his physicality (think: high kicks in fringe vests and cowboy boots) but they also made Ken the essential visual icon of the film.

Mark Ruffalo in Poor Things

Mark Ruffalo’s performance as Duncan Wedderburn in Poor Things is a masterclass in vanity and vulnerability, and his costumes pull double duty in selling both. As an egotistical bon vivant, Wedderburn is adorned in flamboyant late-Victorian getups—lavish cravats, flowy shirts, richly patterned waistcoats, and tailored trousers. No detail is spared: each look is accessorized with extravagant facial hair and perfectly coiffed hair.

Ruffalo uses these costumes to fuel his character’s performative bravado. His peacock-like attire practically demands attention in every scene, amplifying Wedderburn’s arrogance and comic self-importance. As things unravel, so too does his appearance—wilting collars, crooked cravats, and ever-messier hair visually track his growing desperation and diminishing composure. The transformation is not just in the mannerism but in the costuming, which becomes as much a narrative device as dialogue or score. The costumes heightened Ruffalo’s physical and comedic performance, making every unraveling thread part of the storytelling.

Bradley Cooper in Maestro

Bradley Cooper’s portrayal of Leonard Bernstein in Maestro required a complete transformation, accomplished in large part through an extensive range of period-specific wardrobe. From the 1940s through the 1980s, Cooper moves through a series of meticulously reproduced suits, turtlenecks, conducting tails, and casual-wear of each era.

Bernstein’s persona—part bohemian artist, part celebrated maestro—lives in the details: the flamboyant scarves, the open-collared shirts, the stylish horn-rimmed glasses. These pieces allow Cooper to physically communicate Bernstein’s passion and intensity. In conducting scenes, the formal monochrome attire and flowing tails give Cooper’s expressive movements added drama, while domestic scenes soften with relaxed knitwear and pastels, signaling intimacy and vulnerability.

Cooper’s chameleonic shifts between these different styles serve the film’s sprawling timeline and are essential to charting the arc of Bernstein’s public and private personas. The clothes never become mere decoration—they act as a visual shorthand for Bernstein’s ambition, creative spirit, and contradictions.

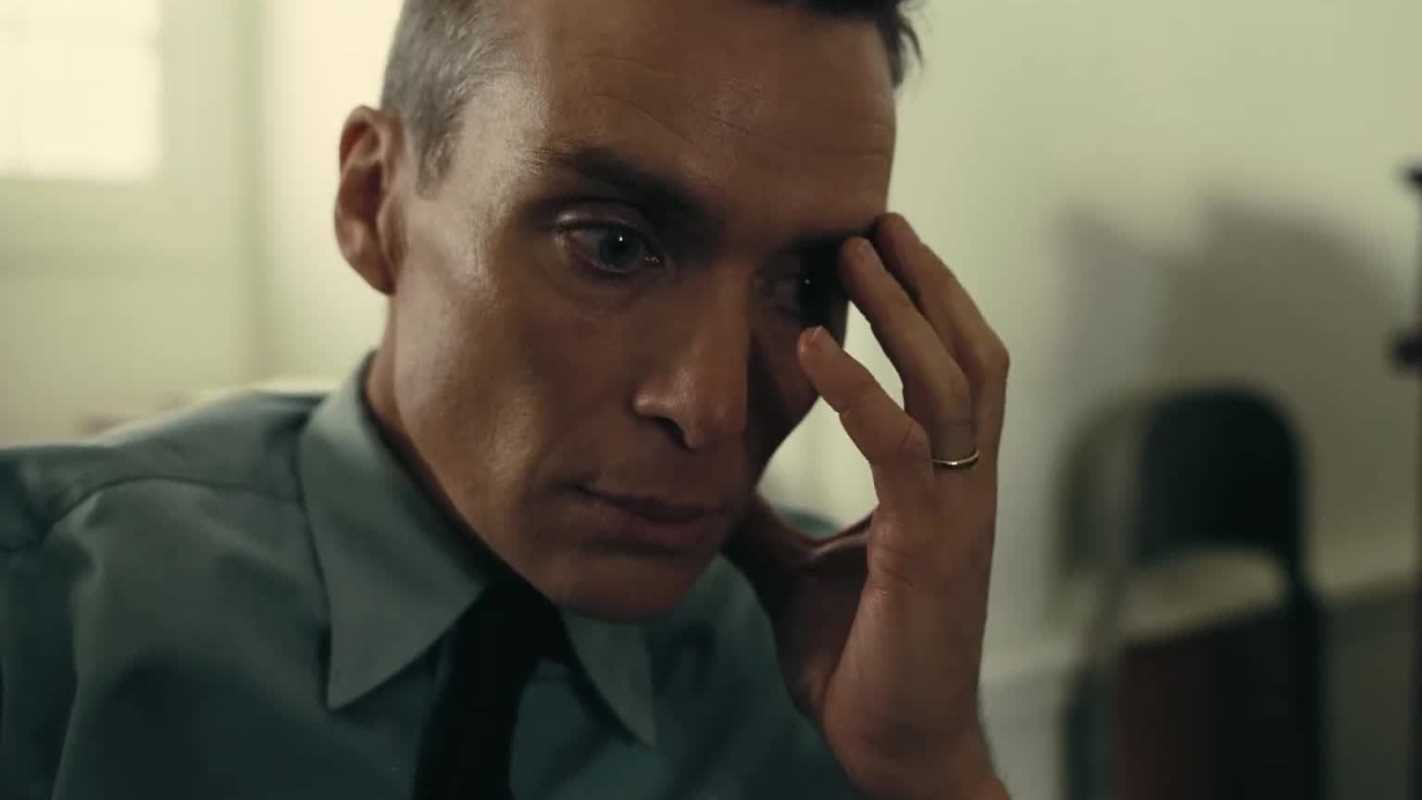

Cillian Murphy in Oppenheimer: The Power of Period Wardrobe

Cillian Murphy’s Best Actor-winning performance as J. Robert Oppenheimer in Oppenheimer is a study in transformation, where every detail of his appearance amplifies the character’s complexity. Murphy’s portrayal draws heavily on the scientist’s distinctive personal style—a silhouette rooted in the mid-20th century, marked by meticulously tailored three-piece suits, slim ties, and the ever-present wide-brimmed pork pie hat.

The wardrobe does more than set the historical scene; it becomes an extension of Oppenheimer’s intellectual rigor and inner turmoil. The severe lines and muted colors of his suits echo the character’s intensity, precision, and haunted genius. The structured tailoring imposes a sense of discipline, mirroring Oppenheimer’s own adherence to scientific method, yet it simultaneously hints at the emotional walls he erects. The crisp white shirts and narrow lapels contribute to an image of austerity, while the hat—an icon in itself—symbolizes both his authority and the isolating burden of his role in history.

Details like pocket watches, understated cufflinks, and occasionally disheveled collars further humanize his edges, subtly indicating moments where the weight of responsibility cracks the polished façade. In tense scenes of moral reckoning, Murphy’s posture within those meticulous layers shows the tension between control and unraveling—a tension essential to Oppenheimer’s character.

By inhabiting these period-accurate garments, Murphy not only visually transports the audience to the 1940s but uses clothing as a conduit for performance, letting the physicality and symbolism of the wardrobe deepen the narrative. His collaboration with the costume team creates a powerful synergy, making every button, cuff, and crease serve the film’s portrait of genius under pressure.

(Image via

(Image via